Many years ago, when I was probably in my mid-twenties, I had a strange kind of epiphany while spending an African summer evening home alone at my folks. They were out, I can’t remember where, and I was still living with them – enjoying time to myself in their spacious and rather luxurious home. It was a beautiful summer evening. I made myself dinner (some sort of rice stir fry, with a decent amount of rum thrown into the sauce – I don’t know why, I just thought it would be nice. It was.). I sat down, finished my dinner, and then decided I wanted to listen to some music.

My dad has a pretty great hi-fi set up. I remember with much fondness the days, when I was in my preteen years and early teens, when I would go with him to various upscale hi-fi stores and join him in his endless hunt for the best speakers, the best tape player, the best vinyl set up, and the best everything sound and technology (and his budget) could allow. We would crowd into these dark and mysterious demo rooms, and sometimes he would bring his own record with, and he’d ask them to pop it on, and then we’d sit down and he and I would just listen to the music and critique the quality of the sound.

“What did you think of that one, son?” he’d ask me. And I’d pretend I knew the answer. “Yeah dad. Really nice bass on that amp.”

He would stop and think. “Hmmm. But it can be better.” Then he would turn to the attendant. “Let’s try those Mission speakers again… and maybe afterwards the Celestions.”

I would listen along with him, and every time he would make a comment or ask me about my thoughts, I would learn some more. Eventually I’d get a little courageous and ask the attendant, “Can you fiddle with the EQ? Maybe put the top end up a bit.” My dad would smile, or not say anything – the latter making me feel like he thought it was a good idea and approved of my suggestion; that he was taking it seriously, and so should the attendant.

That night at my folks, while eating my dinner, I reminisced about these times with my dad, as I still often do, as they were good times when I felt he and I were connecting over a mutual passion, that being music – and actually that we were doing far more than just connecting over music but were actually connecting like father and son. I suppose my passion and love for music really comes from him. From an early age he exposed my brother and I to all sorts of music – and he would tell us things about what we were listening to and what it meant, and what made the sound good, and educate us without making it into some sort of lesson. I would always listen eagerly and learn.

In later years, my dad would get music DVD’s and we would watch them together late into the night, commenting on the performance, the sound, where this or that group is these days, and what made or makes them so good.

I cherish all these times deeply.

So that night I thought to myself that I would scratch through my dad’s vinyls and pull out some of the old classics I grew up with as a kid. This was a time in my life, as I think most people in the ‘quarter’ part of their life go through, when you start trying to link your present identity back into your identity as a kid. During your teenage years you go through a time when “new” is always better – your music is better than your dads, your generation is smarter and cooler, and that old generation doesn’t really know much. You go through a time of breaking out of your childhood, and everything you do is an effort to do that. That breaking out is healthy, but sometimes it’s done in an unhealthy way.

But then you start to settle and you start to try and link who you have become with who you always were – you start to appreciate the fact that your dad and mom’s blood also runs through your veins. As a young man, you start looking for that connection to your dad again – and you find that somehow that connects you to yourself better. So you go back to the things that you find do that for you.

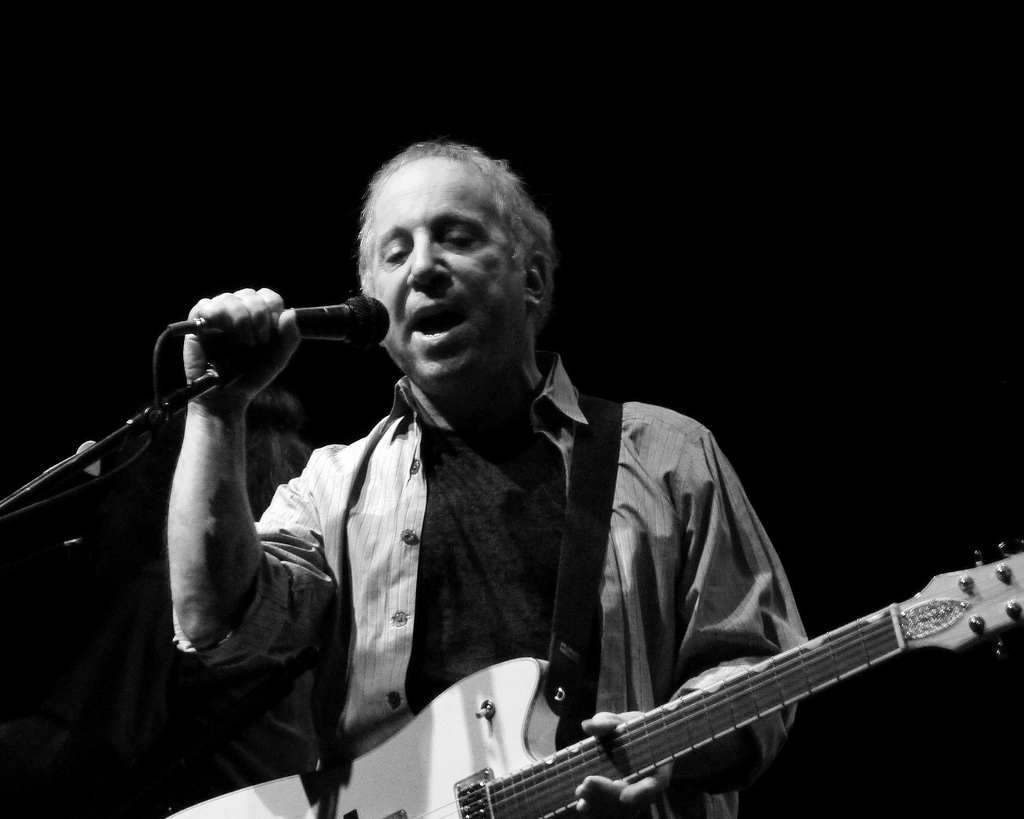

So this was a time in my life when I was, without actually realising it, beginning to collect the music of my childhood. The music I would hear on the radio when I was six years old. Nostalgia eventually becomes an old, reliable friend. Phil Collins, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Pink Floyd… these were the names my dad used to have on vinyl and tape. I would mix them with some of my own favourites from my childhood – Aha, Tears for Fears, and other music from the 80’s.

I had, probably a week or two before this, bought Paul Simon’s classic album, Graceland on CD. (Yes, this was during the CD days.) So this night, as I rummaged through my dad’s vinyl collection, I was presented with something I had never seen or heard before: Paul Simon’s The Rhythm of the Saints.

I knew a fair amount of Simon’s music at the time. I knew there wasn’t just Graceland, but there was his whole original stint with Garfunkel, and “that album” with that song “Allergies” on it (a song I liked as a kid because I grew up with intense allergies). But what was this? I looked at the copyright and read the insert. So this was after Graceland? Well, why had I not actually heard about it?

Graceland was a big deal growing up, because I grew up under apartheid. Simon coming to South Africa and recording with black musicians was something I remembered hearing the grown-ups speak about with strange, hushed or excited tones. I never understood why my uncles and older cousins spoke about it like they did until I got older, of course. But the point is simply to state that I knew all about Graceland – but this The Rhythm of the Saints album was something I had never heard about before.

I was soon to discover that not only had I ever heard about such an album, but never in my life had I even ever heard music like it. From the very first bar of the album – military-like, marching band drums that are soon coupled with what sounds like over a dozen more pulsating drums in the background… (the song is “The Obvious Child“) I sat dumbfounded at what I had just discovered. You could lead music melodically with percussion? (I’m a guitarist.) While I’m sure I had thought of it before, I don’t think I had ever heard it done quite so extraordinarily.

It’s the sound of it that makes all the difference. Somehow, Simon managed to instantly create a sense of mystery and beauty through sound and melody, wrapped up in lyrics that completely and utterly described my frame of mind and the sense I was feeling about my own life that evening.

Sonny’s yearbook from high school

Is down on the shelf

And he idly thumbs through the pages

Some have died

Some have fled from themselves

Or struggled from here to get there

Sonny wanders beyond his interior walls

Runs his hands through his thinning brown hair

The song often repeats the line, “Why deny the obvious child?” For me, the obvious was that I was was also going to get old, and it didn’t matter what I thought about it. It was happening and it would happen, and I would, in my own way, become my dad.

When track 2 hit I remember physically standing up and laughing, staring out the sliding door to my left at the beautiful summer night sky and its immortal stars. Why was I laughing? Because it was brilliant. I Can’t Run But is, tonally and melodically, one of the most original songs I’ve ever heard. I finally found something in music I had been looking for, and which I still struggle to find today: something entirely original.

The Rhythm of the Saints’ brilliance is not only its compositions, which are outstanding, but the way it connects you to something deeper and authentic in such a simple way. As an idealist – a born ‘romantic’ in the classical sense – my life is often made up of intense longings that only us artist-types probably really understand. I want to feel connected to life, not just sailing on its waters; intimately intertwined with others and the earth and the universe and God Himself. It’s not transcendence. It’s not that I want to experience something ‘otherworldly’. It’s more that I want to truly experience the world – I want all of life in its most authentic, intimate form. In short, I want to completely devour Beauty itself; be wrapped up in it. The mystical interests me not because it might take me out of the world but because it might finally put me truly inside it.

Paul Simon, I think, gets this. Somehow he managed to translate it into his music. From Graceland onwards he found a way to create music that takes you not to another world but to the world as it is – as it really is. Some artists try to do that by making you face the grim realities of life. They make you face sadness, loss, and despair. Others try to remain more positive. But Simon… somehow Simon actually does the thing that artists and musicians and writers try to do. He makes you feel sad and happy all at once. He taps into joy and sorrow all at the same time, and through doing so, puts you into the world as it really is: beautiful. Of course, sadness and sorrow isn’t beautiful, but the point is that “joy always comes in the morning.” (Psalm 30.) Simon makes you hopeful. He makes you look at the world and see that beneath all the pain and difficulties there is still beauty and mystery. He makes you acknowledge those longings you felt as a kid and realise they were, and still are, real.

And that’s why Simon’s music has, since then, shifted my world. Every time I listen to The Rhythm of the Saints, a strange feeling of contentment fills me. I realise that, perhaps, the longings of this life are precisely the point. I see once again how the ordinary things of life are actually the things designed to connect me to God and to others. I see once again the beauty underlining every relationship. I am able to remember what matters: the people in my life, especially those that are close to me. My marriage is not just a marriage, but it’s a real relationship with a real person who I really love and who really loves me. I connect again to the real, the authentic, the true depth in life.

I don’t know how Simon does it, but he does it. Even his later albums – like his new In the Blue Light do it. Perhaps not as well, at least for me, as The Rhythm of the Saints, but somehow Simon figured it out and didn’t ever really lose it. Some artists have that one album or one book that does it. Simon managed to continue to do it.

It was Paul Simon’s birthday a few weeks ago and I started writing this then as a tip of a hat for his birthday. (It’s probably ended up being more of a hat tip for my pops though!) He has recently said he is retiring from music. In explaining why, he says that, “When I finished that last album, a voice said ‘That’s it, you’re done.'” I think he is probably right: there’s only so much of this you can do before you just start repeating yourself. Somehow, when I listen to Simon I get the sense that it’s not about him but about the music and the connection to life it brings. That’s the kind of thing I would love to emulate in my own art. For me, I hope that somehow I can do what he did musically through my writing – that somehow others would get that sense of connection to life through my writing. It’s not about me being a brilliant writer, it’s simply about bringing that connection to people; giving them something that does that for them. I’ll then feel as if I’ve done my job and fulfilled my call.